Interview with Gabriela Handal and Leo Lammie

In my previous article, I explored how the viral wave of Ghibli-style AI portraits took over social media and what that says about our relationship with nostalgia, art, and emerging technologies.

After publishing, I wanted to expand the conversation by inviting two artists I admire, Gabriela Handal and Leo Lammie, to share their thoughts. Their responses reveal not only artistic insight but also personal tensions and ideas around creativity, ethics, and AI.

Gabriela Handal is a Panamanian artist based in Brooklyn. Her work explores the human figure in all its strange beauty. Through self-portraits, surreal long-necked characters, and delicate depictions of insects and animals, she draws to stay close to nature and everything it teaches. Creating, for her, is a way to study and honour the natural world.

View this post on Instagram

Leo Lammie is a Panamanian multidisciplinary creative based in Panama, with over 20 years of experience in branding, digital marketing, and product development. His work blends technology and storytelling, with a focus on UX, AI, and game design. He’s an international speaker, an innovation professor, and someone deeply curious about the future of digital experiences and how people connect through them.

View this post on Instagram

Some argue that these AI tools are built on stolen work, scraped from the internet without consent. Do you think it’s unethical for people to use these tools to generate look-alike art in the style of, say, Miyazaki, especially when it’s just for fun or sharing with friends, not for profit?

Handal’s Response (toggle to read):

– Stolen work?

Part of my issue with this whole thing of copyright or trademark or copying is that long before the image generators existed, nobody has ever cleared up for me what it means exactly to have my work stolen. Not to mention that we don’t need image generators in order to steal work from artists, which has been happening long before the generators were even a spark in the eyes of their makers.

Either way, does it mean that Target has t-shirts printed with an image of one of my drawings and is selling the t-shirts without my knowledge? Does it mean that some print selling store is selling prints of one or more of my drawings without my knowledge? Does it mean that an individual is learning to draw, is looking at my work, imitating the way I make drawings? Perhaps all of the above?

What is it? I don’t know, nobody has ever given me an actual definition of what the phrase “to have my work stolen” means, but “you don’t want to have your work stolen” is also mentioned with an urgent feeling.

I asked an AI that I use regularly, I use Claude 3.7 Sonnet and more recently Gemini 2.5 pro exp 03 25.

For this question I went with Claude, because Gemini was prioritizing paying users. Here is the question and the reply:

- Question: “What exactly is it that people warn artists against when they say “you don’t want to have your work stolen” “make sure you copyright everything” this sort of language? What does that mean? And please also provide an explicit example of a situation in which these things have happened”

- Answer: “When people warn artists about having their “work stolen” or emphasize the importance of copyright protection, they’re typically referring to several specific scenarios:

– Direct reproduction and sale: Someone takes an artist’s image and sells prints/products without permission or compensation

– Unauthorized commercial use: A company uses an artist’s work in advertising, merchandise, or other commercial applications without licensing it

– Passing off: Another creator claims the work as their own, removing signatures or attribution

– Derivative works: Someone modifies the original just enough to claim it as new while clearly copying the core elements

Here’s a concrete example that illustrates these concerns:

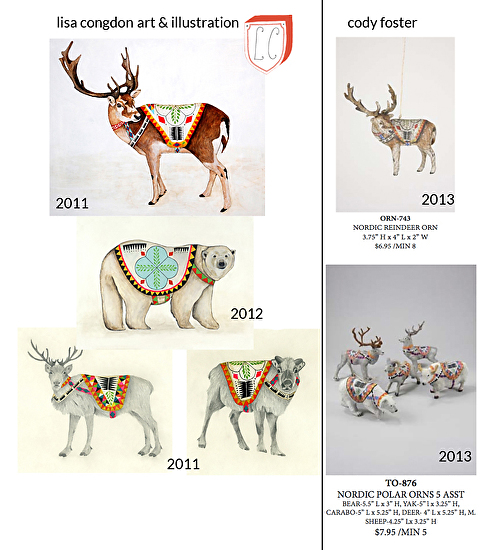

In 2011, artist Lisa Congdon discovered that her illustrations were being reproduced on wall decals by the company Cody Foster & Co. without her permission. The company had taken her distinctive folk art-style illustrations from her online portfolio and was selling products featuring these designs without contacting her, licensing the work, or providing attribution or compensation. When confronted, the company initially denied wrongdoing. Only after public pressure and legal threats did they address the situation.

This case demonstrates why artists are concerned – someone literally took Congdon’s images, incorporated them into products, and sold them for profit without her knowledge or consent. This isn’t an issue of inspiration or similar style – it was direct appropriation of specific, identifiable works.

Similar situations happen frequently enough that many professional artists have experienced some form of this, which explains the protective stance many take regarding their work and why copyright registration (which provides stronger legal remedies) is often recommended for professional artists.”

This example, as you can read, is from before generators were doing anything. Upon looking it up, I am extremely unimpressed, and think the same thing I do almost always when these alleged stolen art situations surface: Lisa Congdon didn’t come up with those images out of nowhere, they look like out Scandinavian themed Christmas illustrations. The images and sculptures made by Cody Foster are far from exact reproductions, though they are similar, but they also look like Scandinavian themed Christmas illustrations. The Cody foster images and sculptures could just as well be what an amateur artist who likes Lisa’s work made while learning to become a better artist or they could be what an artist made because they also like Scandinavian folklore.

I think the issue with the generators is much more similar to this than straight up reproduction of images, theft, and forgery, which is then a segue into inspiration, referencing work, learning how to make images, individuating oneself from the things one used to copy to try to learn to make one’s own images, and the inner workings of creativity itself. The last of which is not understood and I believe no one who says they understand.

Where is the credit or compensation from Congdon to all the Scandinavian folk art that she is obviously referencing in her images? Or the 60’s and 70’s posters that she is obviously referencing in some of her other work? Nowhere, of course.

I find it unbearably hypocritical and short-sighted that we ourselves learned to make images via both copying AND imitating (I did it myself, AND both in undergraduate and graduate school, and I still occasionally do it, because one is never done learning, after all), but we don’t want the generators or other people to learn that very way.

– Unethical?

In the specific example of not maliciously reproducing images for fun, while also not being for the purpose of selling them, no, it’s not unethical.

Also, they are images which have not been made by Studio Ghibli or Miyazaki, they imitate the style and these two are different.

Trying to legally copyright or trademark something as vague and abstract as style is incredibly slippery, short-sighted, and extremely dangerous.

The Gibli trend is also free advertisement for Miyazaki and the studio, but this aspect of imitation, whether by generators or other humans, is never considered, and its value is completely forgone. Advertising is not cheap! There may have even been a surge of people renting/streaming Miyazaki’s movies or getting merchandise during the peak of the trend! Or maybe “delivering” Studio Ghibli to people who had never heard of the studio or Miyazaki. But who is really keeping track of these things.

There are also situations where an artist actually shoots themselves in the foot because they were “protecting” their material, but whoever was using it was actually serving as a massive marketing campaign that benefited the originating artist.

I also asked Claude.

- Question: “Are there any cases which are kind of the opposite, where an artist’s work was being used by someone, and regardless of the circumstances, it ended up being massively beneficial to the artist who originated the work? And also, a similar situation as the one I just outlined, but the artist wanted to legally “protect” their work and so they ended up kind of screwing themselves by not allowing the marketing to take its natural course?”

- Answer: “Unauthorized use that benefited the original artist:

– Shepard Fairey’s Obama “Hope” poster – While Fairey ultimately faced legal issues for using an AP photographer’s image without permission, the poster became iconic and dramatically elevated the photographer Mannie Garcia’s visibility. Though contentious, the exposure led to new opportunities for Garcia.

– Richard Prince and Instagram – Controversial appropriation artist Richard Prince printed and sold Instagram photos from various users without permission for substantial sums (up to $100,000). While legally questionable, some of the photographers whose work he used reported gaining significant followings, gallery interest, and career opportunities from the publicity.

– Music sampling culture – Many early hip-hop artists whose work was sampled before legal frameworks were established later benefited enormously from the renewed interest and exposure. James Brown’s music became highly sampled, which revitalized interest in his original recordings.

Artists who limited exposure to their detriment:

– Prince’s streaming resistance – Prince famously fought against having his music on streaming platforms and YouTube, demanding strict content control. While principled, this decision limited his exposure to younger generations during a critical period of digital music adoption.

– The “Streisand Effect” – Named after Barbara Streisand’s attempt to suppress aerial photographs of her home, which only drew more attention to them. Some artists have similarly tried to aggressively remove unauthorized uses of their work, only to generate far more interest in the very content they wanted to suppress.

– George Lucas and fan films – Lucas’s initially aggressive stance toward Star Wars fan films was later relaxed when he realized the fan community’s creative engagement actually strengthened the franchise’s cultural foothold rather than diminishing it.”

Your question I think contains both circumstances: I suppose it could be argued it’s the companies who make the generators that are indirectly (key word: “indirectly”) profiting if they have users who pay for the service of the generator making images in the style of Studio Ghibli, though a lot of them are free. The individual user is not profiting, and I agree with you that the user is not using the so-called Ghibli-fied images maliciously.

Extra question: Why is it the AI companies who are getting grief, and not the users who are prompting the device, directly instructing it for the images that it then generates? Why is the user exculpated completely?

The issue of whether the companies making the generators are wrong for using images scraped from the internet is grey for me, because of information in Terms and Conditions of different platforms that I have never read and most artists have never read, and even less lay-pepole have read. Additionally, I have serious doubts about whether most artists actually grasp the concepts of copyright, trademark, fair use, and their ilk in order to make the argument that their images are being used without the use of these legal terms. I certainly don’t grasp the terminology.

I asked Claude about this, too.

- Question: “What can you tell me about the explicit information in Terms and Conditions of social media like, for example, Instagram, in terms of images one uploads? How can Instagram use those images? And then what does that mean for those images being “scraped” for teaching image generators how to make images?”

- Answer: “I’d be happy to discuss Instagram’s Terms of Service regarding user-uploaded images and the implications for AI training datasets.

Instagram’s Terms of Service explicitly grant them a very broad license to your content. When you upload images to Instagram, you:

– Retain ownership of your content

– Grant Instagram a non-exclusive, royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable, worldwide license to host, use, distribute, modify, run, copy, publicly perform or display, translate, and create derivative works (?!?!?! My emphasis, and question and exclamation marks) of your content

This license is quite extensive and allows Instagram to:

– Use your photos in various ways across their platform

– Allow third parties to use your content (sub-license)

– Create derivative works from your photos (?!?!?! again, my emphasis, and question and exclamation marks)

– Use your content worldwide without paying you

Instagram’s terms don’t specifically address scraping for AI training, but the broad nature of the license could potentially encompass this use case.

Regarding AI training datasets and image scraping:

Many large image generation models have been trained on datasets that include images scraped from public websites, including social media platforms. This practice raises several concerns:

While Instagram’s terms grant them extensive rights, they don’t necessarily extend those rights to third parties scraping the platform without Instagram’s permission

Even if images are publicly accessible, using them for AI training may exist in a legal gray area regarding copyright and licensing

Recent litigation (like cases against Stability AI, Midjourney, etc.) has challenged the practice of using scraped images for AI training without explicit consent

If you’re concerned about your images being used for AI training, you might consider:

– Using more privacy-restricted social media accounts

– Adding watermarks to your images

– “Understanding that once content is online, it’s difficult to control completely” (my emphasis)

To finish:

I think that, just as the Ghibli-fying of images trend will pass, so too will the generators needing lots of images to learn to make new images pass. The devices are, after all, just learning.

It’s yet another parallel with human learning: once you learn addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, you move on to more complex mathematical calculation and those original basic operations are but an afterthought.

I think we are actually really screwing ourselves by hindering the Artificial Intelligence in different ways (don’t say these words, don’t generate these images, don’t use these images for learning), instead of letting its course of learning run the path it will into whatever its “true form” will be. We don’t know how much potential we are missing out on by placing those limitations.

Lammie’s Response:

I think the problem usually starts when people begin monetizing the pieces. But there are two ways to look at it. Thanks to so many versions of Ghibli art being shared all over social media, Studio Ghibli’s work is now more well-known by people who had no idea it even existed. So for some artists, it’s an opportunity to gain visibility.

Let’s be honest — people have been imitating Studio Ghibli and monetizing off it for a long time without anyone noticing. So it’s really those imitators who might actually be affected now.

In your view, what’s the impact of these AI-generated Ghibli-style portraits on the way the public understands and values the labor behind hand-drawn animation or illustration? Do you think trends like these distort the audience’s perception of what it takes to actually create in that style?

Handal’s Response:

Lay-people not understanding how Art is made is not a new thing, and it hasn’t since perhaps late 19th Century.

The trite platitude of “anything can be art” and the life of the dissolute so-called artist who makes mysterious so-called art that is impossible to understand, is also not new and its origin can perhaps be found sometime in the early 20th Century. Thank you, Da-da. These two are what I would pin as the culprits of so-called lay-people not understanding the work behind making Art.

This is self-imposed damage.

I don’t accept using AI image generators as scapegoats on which to blame so-called ignorant lay-people for not knowing the effort that goes into making a work of Art, it is our own doing and, again, not new.

I also think a lay-person doesn’t have to know that information in order to appreciate a work of Art. One appreciates Art by spending time with the end result of the labor. Similarly, a ballet dancer does everything in his power to conceal every ounce of effort in his performance, and the audience can imbibe and enjoy the end result of the dancer’s labor.

If somebody wants to know, understand, and appreciate the work and time required to make a work of art, then become an artist make one.

Lammie’s Response:

It definitely distorts it. I’m sure that 65% of the people who created these artworks just to share with friends don’t care whether the original art was handmade or not.

They only care about having a laugh or getting likes at a specific moment in their day. However, from that other 35% who probably didn’t know about Studio Ghibli before, now they might value its work more and understand what they’re seeing.

And probably at least 5% of them will be in line for the next Ghibli movie premiere.

Do you think there’s a risk that exposure to these easily-generated ‘Ghibli-fied’ images could desensitize people to the originality and storytelling behind the actual Studio Ghibli aesthetic? Or might it, in some way, inspire more people to explore traditional animation and drawing?

Handal’s Response:

I think it’s possible it could do both to different people, depending on how much they care about Studio Ghibli or animation in general.

I speculate the trend probably means nothing to somebody who feels no nostalgia for Studio Ghibli’s work, has no particular interest in animation, and no interest in image generators, for example.

I would be closer to this first category, because I think Studio Ghibli’s best work is Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind and have zero understanding of the studio’s popularity based on subsequent work (I watched the movie just mentioned, My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Serive, and Porco Rosso. This last one made me rather uncomfortable and quite confused regarding what the hell is happening in the story)

On the other hand, if someone is very fond of the movies that have come out of Studio Ghibli and has even vague interest in animation, perhaps it is, indeed, possible they would want to go the quick route of trying the generators to “Ghibli-fy” images, maybe even animate some of them. However, I also expect not-so-fickle, actually curious individuals to want to go a lot deeper by making the moving images by hand.

How many people there are in each group is anyone’s guess. Unless someone is actually counting.

Lammie’s Response:

Both, really. You can’t stop people from abusing or immediately devaluing art — but at the same time, I’m sure there’s a small percentage that will develop a new interest in traditional art and hand-drawn illustration, and as a result, in storytelling too.

Both things are going to happen, and it’s inevitable. It’s up to us as artists to choose where we want to put our focus.

What is a question you think most people are not asking themselves when using AI to generate art related content?

Handal’s Response:

I have a few:

- Think about how you feel after generating an image vs how you feel looking at a drawing you made yourself with pencil and paper.

- Think about how you feel looking at an AI generated image vs how you feel when you see a drawing made with pencil and paper by another person with your own eyes in front of you.

- How long did you spend with one or the other?

- How many times did you go back to look at one or the other?

Lammie’s Response:

Haha, good question. I think most people don’t ask themselves anything — they do it because it’s trendy, to get likes (or validation) at a specific moment in the day.

But I do believe that at least a quarter of that crowd does stop to wonder about a few things. To me, the most important questions are:

What will AI do with all our photos once we’ve given them away?

Will the day come when it can produce a full animated movie just from prompts? Will AI-generated art ever be valued or have its own category?

And… what would Miyazaki think of all this?

That last one — if you’ve read this far, I bet you’re asking yourself that question right now.

At the end of the day, AI won’t stop evolving — but neither will our curiosity, creativity, or the stories we choose to tell.

My Reflections

I can’t say I fully understand the impact of AI-generated art or how different parts of society really feel about it. Most of what I see comes from the bubbles I stumble into on platforms like X, Threads, Facebook, and Instagram. Depending on the group, the reactions usually fall into one of three categories:

-

“I hate AI and want nothing to do with it.”

-

“AI isn’t the future, it’s the present. Get on with it or get left behind like a typewriter at the end of the 90s.”

-

“I don’t care. I use it because it makes my life easier and I get what I need from it.”

This is why I think conversations like this matter. I love art. I really do. And I also love technology. It’s easy for me to lean hard into one side or the other. But I’d rather stay grounded and try to understand how the people doing the actual work feel. Otherwise, am I even paying attention?

Reading Gabriela and Leo’s responses made me pause and look at the trend differently. Gabriela’s tone felt analytical and a bit existential. Leo came across as more pragmatic and forward-looking. I appreciated the contrast. Gabriela focused on deeper questions around authorship, imitation, and how we learn to create in the first place. Leo brought up what happens next. What AI might do with our data, and how far it could go.

They both brought up questions I’ll be thinking about for a while.

What’s your take?

Thanks for reading this much.

Suggested Reading

– The Viral Rise of Ghibli-Style AI Portraits: What It Says About Us

Where this conversation started, a reflection on nostalgia, AI, and the Ghibli-style wave on social media.

– Should AI Art Be Considered Art? Interview with Gabriela Handal (2023)

My first conversation with Gabriela on the nature of art and technology, long before this latest trend took over our feeds.